A tale of two valleys

How tech booms fuelled liveability busts in Silicon Valley and Bengaluru

Good morning! A big hello to readers who signed up this week. Welcome to The Intersection, The Signal's weekend edition. This weekend we talk about un-livability in Bengaluru and the San Francisco Bay Area. Also in today’s edition: we have curated the best weekend reads for you.

If you enjoy reading us, why not give us a follow at @thesignaldotco on Twitter and Instagram.

In Bengaluru’s east is an area called Bellandur. It’s home to a toxic, smelly lake—whose literal frothiness has been the butt of social media jokes for years—but also the nucleus of India’s prominent startup founders. Here, product managers, VCs, and CXOs of multinational technology companies live in enclaved villas within Adarsh Palm Retreat, or APR.

APR is the epitome of Peak Bengaluru. Residents Dunzo everything, and founders pitch their next big ideas to investors in a Starbucks or a Third Wave Coffee outlet at ‘The Bay’. All while Yulu bikes criss-cross one another near a busy intersection.

But a brutal reality check awaits this techno-utopianism not far away. The junction here hosts traffic snarls, metro construction, road blockages, and a two-kilometre diversion (U-turn hell) that stonewalls your travel from point A to point B. This too is Peak Bengaluru, where infrastructure hell intersects with aspirational-everything.

Not what a city of the future should look like.

Until the early 2000s, Bengaluru (then Bangalore) was a pensioners’ paradise for its weather, liveability and cosmopolitanism. Fast forward to today, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Global Liveability Index 2022 has deemed it India’s least liveable city. Pakistan’s financial capital Karachi, identified as one of the five least liveable cities in the world, scored better in infrastructure. This was in stark contrast to the Centre’s Ease of Living Index 2020, which bestowed prime ease of living honours onto Bengaluru.

Dissimilar, but equally-dire concerns have gripped a hub located over 14,000km as the crow flies across the Pacific Ocean. The people of Silicon Valley—from where Bengaluru gets its cue cards—are also grappling with a deteriorating quality of life. So much so that 56% of its population wants to leave.

This is the story of how tech, and the changes it brought along with it, changed the fabric of two IT capitals… for the worse.

Bay Area

Sunnyvale is an apt name for a city in the heart of Silicon Valley, at the southern end of the San Francisco Bay Area, where the sky is always blue and largely cloudless. The burgeoning population of Indian techies has earned the city its new moniker ‘Sooraj Nagari’, much the way neighbouring Mountain View—home to Google’s global headquarters—goes by the name ‘Pahar Ganj’.

A drive up the bay along Highway 101, from Sunnyvale to San Francisco city, feels a bit like driving into fog. The sun suddenly vanishes as you enter a city built on hills, overshadowed by clouds. Befitting a city as quirky as San Francisco, the cloud has a name: Karl the Fog. Karl has an Instagram account, a Facebook page and a Twitter following.

Karl isn’t the only cloud hanging over San Francisco these days. The city of tech billionaires and exploding homelessness saw the largest exodus out of the city in the first year of the pandemic compared with any other major American city. US Census data released earlier this year showed a 6.7% population dip from April 2020-July 2021.

Artists and idealists, once a symbol of SF, can no longer afford rents in a city that’s turning into a dormitory for tech employees. The pandemic-induced exodus shows that techies— among the city’s highest-paid residents—don’t want to live here either. San Jose, Silicon Valley’s largest city, saw its population drop below one million for the first time since 2013. “California’s largest cities have been steadily haemorrhaging residents since the start of the pandemic,” East Bay Times journalist Tammer Bagdasarian wrote earlier this week, citing the hollowing out of cities through a pattern of migration called the “donut effect.”

The Donut Effect of Covid-19 on Cities, a paper (pdf) by Stanford University’s Arjun Ramani and Nick Bloom, used data from the US Postal Service and real estate website Zillow to quantify migration patterns across US cities. They found that within large cities like SF, homes and businesses moved from dense central business districts to the suburbs. Relocation around big cities was far more widespread than relocation from large cities to smaller regional cities and towns.

It is this very movement out of SF that prompted city mayor London Breed to worry about the financial impact of the out-migration on the local economy. Meanwhile, Oracle and Tesla have moved out of the Bay Area. And news of Salesforce reducing office space in SF left one resident hopping mad. Abraham Woodliff’s expletive-ridden video, uploaded on social media, made it to the news. He said the city had “f***ed over all the people who did cool sh*t, and gave the city art and culture and life”, like the LGBT community. He also blamed the city for tax breaks to large corporations.

While Woodliff’s ire may have been misdirected at Salesforce (which isn’t leaving the city and didn’t get tax breaks), it holds true for other big tech companies, and he reflects the sentiments of many residents.

The housing crisis has been caused, in part, by SF’s strict zoning laws and the ease with which residents can block approvals to construction projects. SF’s board of supervisors have actually voted against affordable housing projects because they would cast evening shadows over parks.

While tech can’t escape its share of blame for making the city unaffordable, the ‘Not In My Backyard’ (NIMBY) phenomenon is equally to blame, with residents lobbying against any construction that would change the city’s old world charm and replace single-family homes with larger buildings that house more people.

Not surprisingly, the likes of teachers and firefighters find it increasingly hard to afford SF rents.

‘Can Artists Afford to Live in San Francisco Any More?’ was the headline of a piece in SFMOMA’s monthly magazine a decade ago. Unsurprisingly, the first line read: “The rents are too darn high.” Five years ago, the city even launched an artists census to find out how many were left.

It’s ironic that a city at the epicentre of the counterculture movement is now trying to count its dwindling population of artists.

In 1967, over 70,000 young people had gathered on the streets of San Francisco for a summer of rock ‘n roll, psychedelic drugs, anti-war protests, and a free love movement against the status quo and American consumerism. Hippies from college campuses across America converged around the Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood, where they formed communes. The movement gave rise to iconic stars such as Janis Joplin. Now a tourist attraction, the area is unaffordable for artists, much like how the Castro—once the epicentre of SF’s gay rights movment—is unaffordable for much of the LGBT community.

The hippies of the ‘60s were inspired by the Beat Generation, a ‘50s literary movement that was anti-materialist, anti-war, and inspired by Buddhist spirituality. But today, SF writers such as George Denny are looking to leave the city.

“The biggest headwind I face as an artist is that if I ever go on a date, I would never tell a woman I was a writer if I wanted to see her again,” Denny tells The Intersection. People with creative dreams in the city are associated with a lifetime of disappointment, he explains.

Denny’s friends who’d moved to SF during the boom times have now left. Many departed with a purchase agreement to buy real estate in another state. The artist believes that by incorporating the tech community so rapidly, SF became a feudal system comprising of four classes: the tech C-suite, fresh-out-of-college hired recruited at six figure salaries (and fuelling high rents), workers who serve both classes but can’t afford to live there (waiters, drivers, cops), and a fourth class of homeless people.

An increase in crimes like shoplifting and higher costs of security have also shuttered pharmacies in the city. “It’s an adventure trying to get your prescriptions,” Denny says.

Gitanjali Shahani, professor at San Francisco State University, feels the most visible changes can be seen in streets like Valencia in the Mission District. When she first moved to the city 15 years ago, Valencia was gritty and messy, reminding her of the Bombay she grew up in. “There was even a Bombay Ice Cream store in Valencia,” she tells The Intersection. Shahani also recalls Lost Weekend, a video store where you came in, browsed and took your time.

Both Lost Weekend and Bombay Ice Cream are no more. In their place are interior design outlets and stores selling designer hoodies, the iconic vestment of the billionaire tech revolutionary.

Shahani, however, does not believe the city is in decline. To her, the largest problem facing the city is housing

SF has always been more welcoming of the homeless than other parts of the US, providing safety nets for the homeless that are not found elsewhere. Many homeless people are on drugs—not the heady psychedelics of the hippie era, but synthetic opiates like fentanyl that are 50-100 times stronger than morphine. Today’s homeless addicts are a far cry from the young men and women of the ’60s with flowers in their hair, high on LSD and rock ‘n roll, out to change the world.

While protesting the Vietnam War was at the heart of the counterculture movement, the end of the war saw its decline. Flower children also began to suffer from the seamier side of hippie culture. Communal living gave rise to overpopulation and unsanitary living. While ‘Make Love Not War’ was a popular slogan of the time, sharing a bed with strangers, as many hippies discovered–could get you sick. And while drugs inspired poetry and music, an overdose resulted in death. An unstructured life built on love and the absence of rules birthed less than ideal living conditions.

An unexpected legacy of the counterculture movement lies in the creation of Silicon Valley. Many Stanford computer scientists had their tryst with LSD during the ‘60s. Steve Jobs, for instance, grew up in the midst of the counterculture movement, and was among many who were inspired by the Whole Earth Catalog, a bible of the counterculture era, that supported an ideology of self-sufficiency and DIY tools. Its founder, Stewart Brand, was a major link between counterculture and the nascent tech industry. He called personal computers the new LSD.

Silicon Valley owes its ideals of technological utopianism to the culture of the 1960s–a heady belief that tech is inherently a force for good in the world. That belief seems as naive as the idea that a bunch of 20-somethings in loose clothes with flowers in their hair could sing their way to peace.

Bengaluru

Unlike the Valley, Bengaluru’s growth has everything to do with its inability to catch a breath while running a marathon.

In 1985—the year Texas Instruments set up its R&D facility in the city—Bengaluru had a population of 33 lakh, according to the World Population Review. Thirty-seven years later, that has burgeoned to 131 lakh or 1.31 crore. The city’s vehicular population has also breached the 1 crore (10 million) mark, with a 35% increase during Covid-19 lockdowns.

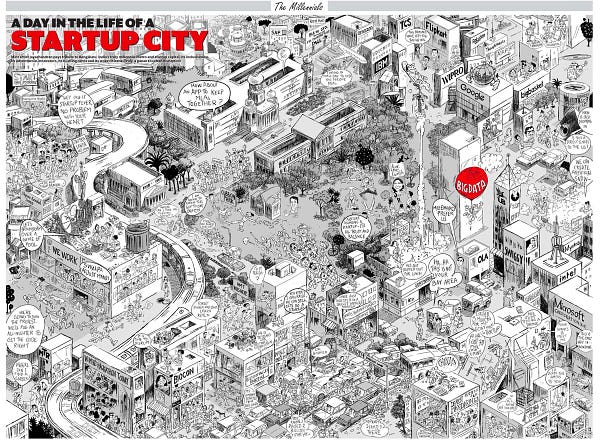

Technology delivered wealth too. The cohort of its wealthy inhabitants has also grown to 352 at last count, of which at least 28 were billionaires. The city is also India’s unicorn capital, with 39 startups valued at more than $1 billion, ahead of Delhi-NCR with 32, and Mumbai with 16, according to Traxcn data.

Yet, gridlocked traffic, doddering utilities (water and electricity), and loss of green cover are testament to Bengaluru’s unpreparedness for this breakneck growth. So says K Jairaj, a retired IAS officer who served as commissioner of the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP).

“Bangalore wasn’t prepared for such a big urban explosion,” Jairaj tells The Intersection.

The explosion he refers to is migration. Over 42% of Bengaluru’s population comprises migrants, making it the city with “the second-largest migrant population after Mumbai.” This number would have boomed further after the birth of the gig economy, which cemented Bengaluru’s place as “the city of opportunity,” to quote Jairaj.

But local urban planner and architect Naresh Narasimhan doesn’t buy the “unprepared to deal with an explosion” argument.

“For the last 20 years, the government has been saying that Bengaluru is growing too fast. So, there is no way they wouldn’t have anticipated it. Everyone had foreseen it,” he says.

Brand consultant Harish Bijoor concurs. To him, the city is a perennial work in progress. Consider that the BBMP spent nearly ₹23 crore on road repairs in preparation for PM Modi’s visit last month, only for the relaid Kommaghatta Road to become potholed just a week later.

“The city will become a megacity, but the attitude will not be a megacity attitude,” Bijoor tells The Intersection. “Bengaluru hasn’t had a master plan since 2015, so there’s a lack of direction whether it’s to do with policy, vision, or implementation.”

This probably explains why you’re having your morning Zoom meetings while stuck at the Silk Board Junction.

During his visit last month, PM Modi announced ₹27,000 crore worth of infrastructure projects for Bengaluru. While citizens welcomed this shot in the arm, not everyone is gung-ho about allocation and execution.

Mohandas Pai, the former Infosys director and poster boy of Bengaluru’s tech boom, feels the rot runs deep. “There’s a high degree of corruption in every wing: roads, governance and garbage,” Pai tells The Intersection. “The government collects taxes from urban areas, but invests them in rural regions.” He nevertheless thinks the city’s un-livability is an exaggeration.

What if, just what if, the BBMP adopts the Mumbai Metropolitan Region model, where different municipal corporations govern specific divisions? Harish Bijoor believes Bengaluru should be “decentralised” or overseen by different BBMP divisions for efficient management. But Dr Ravindra Adi, former chief secretary of the Karnataka government, reckons that’s easier said than done.

“There is no coordination between governing bodies today, even though it’s been a longstanding problem. Governance was better earlier,” he tells The Intersection.

Former BBMP commissioner K Jairaj believes population distribution to satellite cities such as Kengeri and Yelahanka is critical for Bengaluru to redeem its liveability. However, people still pour into Bengaluru for work, meaning that economic dispersal, not mere population distribution, is better placed to solve the mess.

“For this long-term solution, Tier-2 cities [along Bengaluru’s radius] need to be developed,” Jairaj says. That is not happening.

The tech industry’s influence has created a kind of donut effect in Bengaluru too. The peripheries of the city—beyond Whitefield and Electronic City (which themselves were beyond the outskirts at one point)—are burgeoning as entrepreneurial hubs, attracting founders, tech talent, and the vast armies of support service providers. There is a frothiness to it all. Like Bellandur lake. But the hustle is here to stay.

(With reporting from Debarati Bhattacharjee and Roshni Shroff)

ICYMI

Too hot to handle: How far are people willing to go to get the social media handles of their choice? Find out in this bonkers story about users with OG handles— ones that are short or comprise one word and are therefore valuable, like @jack. People with OG handles are either offered big money to give up their usernames, or hounded if they choose to hold onto them. This longread is about the black market for OG handles, and the harassment experienced by ‘Handle Heroes’.

Holy Guacamole! The avocado has survived time. It could have been a thing of history with the Ice Age but it went on to become a favourite tropical delight. All thanks to a California postman in the 1920s who accidentally created a delicious mistake. This story in The Marginalian traces the origins of the fruit.

Clipped Wings: Travellers may be ready for a vacation vengeance, but their wanderlust dreams will have to wait. It is chaos central out there, what with the aviation industry struggling to take off without a hitch. The state of affairs is similar from country to country, with the industry hoping the kinks will iron out over time.

Worth Flex’in: The elephant's rather versatile trunk is all down to its skin. The trunk was expected to be uniformly muscular, much like the human tongue. According to a new study, the flesh at the top of the trunk is flexible by at least 15% more than the underside. FWIW: this study will also help engineers who work on soft robotics. Bonus: footage of the elephants completing tasks.

Dune City: Science fiction has often tickled the imagination of billionaires. Jeff Bezos’ and Elon Musk’s galactic exploration dreams and brain enhancement chips are born in fantastic tales of science. But nothing matches the ambition of Saudi Arabia’s Prince Mohammed bin Salman, often known only as MBS. The crown prince is building Neom, a futuristic city that will combine Hollywood sci-fi fantasies and environment consciousness in the unforgiving desert of his country. For instance, it will have flying cars as well as commuter canals to swim to work! Bloomberg Businessweek reports on the capriciousness and wastage in the Tughlakian project of princely fantasy.

Scripting Politics: Vincent Bollore’s rise as an influential media baron in France has set tongues wagging about his deeply conservative beliefs and intentions for French politics, reports Bloomberg. The media jet fuel propelling one of the presidential challengers in the last election, Eric Zemmour, was supplied by Bollore’s empire, Vivendi, which owns CNews, Canal+ and Hachette. Dubbed the French Murdoch, Bollore says he only means business. It's serendipitous for him that the right wing is where the money is in many countries, including France.

Enjoy The Intersection? Consider forwarding it to a friend, colleague, classmate or whoever you think might be interested. They can sign up here.

Want to advertise with us? We’d love to hear from you.

Write to us here for feedback on The Intersection.

As Paul Collier mentions in his book, cities are an agglomeration of skills and talented people. While BLR and SFO have seen a massive technological progress, thanks to the agglomeration, the challenge begins when this progress is concentrated in one region. The biggest beneficiaries are the landlords who benefit vastly from their literal "rent seeking" behaviour in the progress.