The curious case of NeoLacta Lifesciences

How donated breast milk went from public service to tradeable commodity

Good morning! A big hello to readers who signed up this week. Welcome to The Intersection, The Signal's weekend edition. This weekend we talk about the companies profiting from human breast milk. Also in today’s edition: we have curated the best weekend reads for you.

In 1987, the year Margaret Thatcher won her third term to become Britain’s longest-serving PM of the 20th century, Dr Armida Fernandez arrived in the UK on a fellowship. It’d been a rough decade for the National Health Service, what with public healthcare being a target of Thatchernomics. But the engines of a donor-driven, nonprofit enterprise chugged despite looming welfare cuts.

That enterprise was the human milk bank.

Fernandez watched as healthcare workers in Oxford and Birmingham cycled to women’s homes, collected donated breast milk, then pasteurised and stored it in local banks. Far healthier than infant formula, this donated milk saved the lives of premature babies and newborns who couldn’t suckle due to various complications.

Two years after she’d taken notes in the UK, Dr Fernandez established Asia’s first human milk bank at Sion Hospital, Bombay.

In the 33 years since, 80-and-counting nonprofit human milk banks mushroomed in India. Because they’re critical in a country with the highest number of preterm or premature births (which in turn is a risk factor for neonatal mortality), these banks are mostly attached to public hospitals. They either provide milk for free, or charge a nominal sum for a few hundred ml.

That changed when two private operations—Amaara Milk Bank and NeoLacta Lifesciences Pvt Ltd—entered the picture in 2016. The first, a joint venture between Fortis La Femme and the Breast Milk Foundation, is the brainchild of a shadowy group. The second is not only thriving despite having its licence cancelled, but runs a for-profit human milk enterprise in the UK called NeoKare.

The Intersection looks at how NeoLacta Lifesciences got to the point of charging nearly ₹5,000 for 1g of human milk fortifier–on the back of regulatory blunders, sops for doctors, and the alleged exploitation of disadvantaged women.

Backdrop

There’s nothing new about breastfeeding and surrogate breastfeeding/wet nursing, but both got a fillip after 1981. That was when 118 countries passed the World Health Organization’s ‘International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes’. This ground-breaking code cracked the whip against heavyweights like Nestle. Until then, manufacturers of infant formula had indulged in unscrupulous practices, especially in the global south. These included advertising formula as better than mother’s milk, having sales reps dress as nurses, and incentivising paediatricians to discourage breastfeeding. About 66,000 infants died in 1981 as a result of deceptive baby formula marketing. The issue was tinderbox enough for people to boycott Nestle throughout the 1970s-80s.

Dr Arun Gupta, then a practising paediatrician in Jalandhar, remembers the extent to which breast milk substitutes percolated in India.

“Nestle wasn’t just giving free supplies to hospitals and maternity homes, but creating demand with ‘buy 5, get 5 free’ inducements. All this when mothers didn’t even know basics like the lifesaving properties of their own milk, using only clean water for formula, and sterilising bottles,” he remembers. Gupta has been the central coordinator of the Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India (BPNI) since 1990.

After the global pushback and the WHO code, India passed the Infant Milk Substitutes, Feeding Bottles and Infant Foods (Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution) Act— better known as the IMS Act. This Act (pdf) bans the promotion of breast milk substitutes for children aged two years and younger. The promotion of breastfeeding eventually led to the setup of more human milk banks. These must follow the operational and technical protocols specified in the National Guidelines on Lactation Management Centres in Public Health Facilities (let’s just call it NGLMC for short).

Tl;dr: Corporations, breast milk banks, and healthcare practitioners and staff must adhere to the IMS Act and the NGLMC.

If only.

Chain of events

On July 3, The Times of India broke the news that NeoLacta Lifesciences was selling its products despite the cancellation of its Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) licence. NeoLacta had obtained an FSSAI licence for ‘dairy products’, which the regulator classifies as food. But FSSAI doesn’t permit the sale of breast milk.

Yet, NeoLacta continues to operate after the FSSAI setback. Because in November 2021, the AYUSH ministry granted it a licence for ‘Naariksheera’ or breast milk. The company is the only one in Asia selling breast milk and its derivatives for profit.

The regulatory hopscotch is particularly damning because the NGLMC, which was compiled by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare or MoHFW, prohibits the commercial sale of human milk. From page six of the guidelines (pdf):

“DHM [donated human milk] cannot be used for any commercial purpose. It is to be provided to the newborns/infants admitted in the health facility where CLMC [Comprehensive Lactation Management Centre] is situated, after all the procedures enlisted in the guidelines are followed.”

By legitimising NeoLacta, the FSSAI and AYUSH themselves violated MoHFW’s human milk guidelines.

Here’s why all this matters. Depending on variables such as the hospital (public or private), stock, etc., banked milk costs anywhere between nothing to ₹500-plus for 50 ml. TOI claimed NeoLacta charged ₹4,500 for 300 ml of frozen breast milk, which works out to ₹750 for 50 ml.

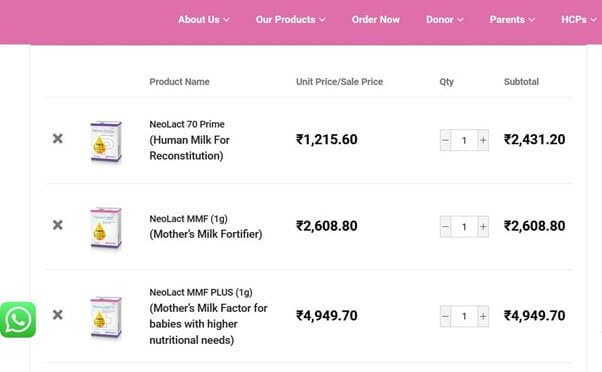

Two units or 20 sachets of NeoLact 70 Prime, which is reconstituted human milk powder, costs ₹2,431 (it’s 400 bucks more on Amazon). The 1g human milk-based fortifiers—meant only for premature babies with special nutritional needs or serious conditions—are far more expensive. At the time of adding these items to cart, NeoLacta did not ask for a prescription or copy of a diagnosis.

As the government-appointed compliance watchdog for the IMS Act, BPNI had taken note of NeoLacta as far back as 2020. That year, a bombshell study answered questions about how NeoLacta sourced its milk. The company allegedly hired rural NGOs that (ironically) focus on women’s health and empowerment, and got them to lure underprivileged mothers with cash, food packets, and kitchen appliances. These women, paid ₹8 and upwards per ml of milk, weren’t given breast pumps. They expressed milk by hand. Since their remuneration hinged on the volume of donated milk, it’s possible they may have given away milk that could’ve otherwise been used to feed their babies.

This exploitative business model transformed a public service into a product sold at 2x and higher margins. Financials sourced from Tofler show that NeoLacta’s EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) in 2020 had jumped over 116% over the previous financial year.

Incentivising women to sell breast milk is in contravention of the NGLMC, which says: “Breast milk donation… will be purely a voluntary activity… donation of breast milk would be non-incentivised and no benefits whatsoever in cash or kind would be provided to the donor mother.”

Which is why BPNI’s Dr Arun Gupta alerted the FSSAI in 2020. But it was only a year later that he grasped the full scale of NeoLacta’s legitimisation, thanks to a whistleblower who went by ‘Alert Citizen’:

Dear Sir,

This is to bring to your notice that Neolacta Lifesciences, a Bangalore based company, is continuing to sell its products, which are human milk derived, in the market in-spite of its license no. 11217302000458, which has been cancelled since Jan'22, by FSSAI authorities…

We fail to understand how a company can continue to sell human milk products in the market under a suspended license.

Please do the needful to curb this issue.

Regards,

Alert Citizen

Only upon pressing the FSSAI further did Gupta learn about the AYUSH licence, and why the company had remained untouched.

If that wasn’t enough, NeoLacta Lifesciences also violated the IMS Act with Nestle-like tactics. The National Neonatology Forum of India (NNF)—the country’s premier forum for paediatricians and neonatologists, or doctors who specialise in newborn care—had events sponsored by NeoLacta. The company also placed ads in the Journal of Neonatology, NNF’s in-house scientific publication. Former NNF president Dr Ranjan Pejaver once co-authored a 2020 paper with NeoLacta’s chief scientific officer, Dr Vikram Reddy. Published in the International Journal of Pediatric Research, that study recommended NeoLacta products over publicly-available milk banks, yet cited “no conflict of interest”.

The Intersection sent questions to NeoLacta managing director Saurabh Aggarwal, who had this to say about the licence fracas:

“‘Mother’s milk’ was specifically mentioned in the [NeoLacta] FSSAI licence, which was granted in 2017, then subsequently renewed in 2018 for five years until November 2023.”

“Amaara and Aadya sell human milk outside of their hospital without any kind of licence. A commercial private company processing human milk (neslek.com) has a FSSAI dairy licence that does not even mention human milk, but appears to be processing human milk as per their website.”

Aggarwal, however, did not respond to our query about the 2020 study that claimed unethical sourcing of human milk. Questions to the FSSAI, AYUSH ministry, and the NNF went unanswered.

“This whole thing,” laments Dr Gupta, “has become about showing kindness to mother’s milk, not to mothers.”

Beyond banks

Kindness to mothers isn’t common in hospitals. Most neonatal ICUs (NICUs) isolate preterm babies for various reasons. While she recognised the indispensability of human milk banks, Dr Armida Fernandez also knew how critical mother-infant bonding is. Kangaroo care (where a mother holds an infant skin-to-skin against her chest) aids better sleep, weight gain, motor development, and breastfeeding in premature and sick infants. It also increases endorphins in the mother, which in turn boosts the expression of milk. And so, the former dean of Sion Hospital did something few institutions do: she encouraged new moms to spend time in the NICU. Because once kangaroo care is established, a preterm baby may not even need donated human milk.

“Beyond setting up milk banks, hospitals should focus on mother-baby bonding, since that has tremendous implications for infant health,” Fernandez tells The Intersection. “What NeoLacta is doing is totally unethical– exploiting the poor and then selling it at whatever rates it wants. Commercialisation shouldn’t be there, period.”

NeoLacta justifies its prices by claiming to add significant value through proprietary technology. In this 2021 sponsored piece, for instance, it claims to be “the only human milk facility in India to have ISO clean rooms, HACCP certified processes, onsite R&D, chemical and microbial labs and walk-in freezers, which distinguishes NeoLacta from any standard human milk bank.” Company chief Saurabh Aggarwal also told The Intersection that no Indian milk bank “tests each batch for nutrients and contamination,” and that NeoLacta uses “gentle heating and cooling, without using any chemicals, resins, solvents, or processing aids, to ensure retention of micronutrients like lactoferrin, human milk oligosaccharides, IgA and hundreds others. These are all very expensive processes.”

But public banks do test for contaminants. And you don’t need high-falutin everything to provide lifesaving human milk to infants in need. Indian banks may be underfunded and understaffed, but equipment isn’t a pain point. It’s all about protocol: register and screen a donor mother, let her express milk comfortably, collect and freeze the milk, pool it, pasteurise it, test it, and then store and prescribe for babies in need.

What’s the point of gleaming facilities and proprietary technology across a 10,000 sq ft expanse in Jigani if you’re allegedly sourcing milk through exploitative means?

Dr Gupta says BPNI will question the AYUSH ministry about NeoLacta’s licence. But amidst the hoopla surrounding one company, another private enterprise has passed muster.

Amaara Milk Bank, managed by the Breast Milk Foundation and Fortis La Femme, charges about ₹1,500 for 650 ml of donated milk. That’s far cheaper than NeoLacta’s products, but the Srivastava Group (SG), which runs the Breast Milk Foundation, is newsworthy for different but wrong reasons nevertheless. A 2019 investigation by EU DisinfoLab found that the virtually-unknown company masterminded a 15-year disinformation campaign by creating think tanks, UN-accredited NGOs, and propagating fake news websites whose content was repackaged by wire service ANI. Much like its operations, next-to-nothing is known about how SG bagged a joint venture with Fortis to supply donated human milk to Indian hospitals.

Former British PM Margaret Thatcher once assured her country that the NHS was safe in her hands. But Britons joked that her overseeing public health was akin to Dracula guarding a blood bank. NeoLacta and Amaara remind one of this analogy.

Note: The story has been updated to reflect NeoLacta MD Saurabh Aggarwal’s responses.

ICYMI

Storyteller: Talk about dedication. When fantasy novelist Yifan read about the silver mine of Kashin on Chinese Wikipedia, he went down the rabbit hole. He was intrigued to realise that the Russian narratives were either little or non-existent. The Chinese versions, on the other hand, were descriptive. Yifan soon concluded there was no war such as the silver mine of Kashin. It was, in fact, made up by Zhemao, A Chinese woman who wrote Russian history for a decade. A gripping story, this.

Going to the floor: At The Signal, we often tell you about the happenings in crypto. There’s a good chance you’ve read about Three Arrows Capital (3AC) in these pages. But its rise and freefall, as chronicled here by Bloomberg Businessweek, is something of a reflection on the crypto industry in itself. And here, The Guardian speaks to some of the amateur investors who followed the likes of 3AC’s influencer founders Su Zhu and Kyle Davies and lost it all when crypto’s “house of cards” collapsed.

The Science Populist: There’s a good chance some of us have given Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens or Homo Deus a read, or in some cases two. So did neuroscientist Darshana Narayanan. In this detailed Current Affairs piece, she puts Harari* through “serious scrutiny”, and the author doesn’t come out well. Narayanan writes, “Harari has seduced us with his storytelling but a close look at his record shows that he sacrifices science to sensationalism, often makes grave factual errors, and portrays what is speculative as certain.”

Hot mess: The Dijon mustard is often the secret ingredient and a mainstay in French cuisine. French are hit with a rather peculiar crisis: there is a dearth of mustard. Yes, just another casualty of climate change. The war in Ukraine has further clamped down on supplies. Psst: We are only being messengers here. Climate change is also coming for bread.

Lights out: South Africans are living in the dark for more than eight to nine hours a day. One of the country’s most-downloaded apps provides alerts and schedules for power outages. Eskom, the state power monopoly, cannot generate enough electricity to meet demand, and is deploying a byzantine system of rotating outages to avoid the collapse of the entire grid. Why? Eskom is beset by allegations of corruption and mismanagement.

Circle of life: Trolley parks are now a relic of a bygone era. Today, they've given way to larger-than-life theme parks. It was once a symbol of urbanisation—families and workers coming together on weekends to forget the routine of everyday life. Then Disney came into the picture, and there's been no looking back since.

Update: The author Yuval Noah Harari’s last name has been updated to reflect the correct spelling. It was misspelled as “Hariri” in the third ICYMI. We regret the error. h/t to the alert reader.

Want to advertise with us? We’d love to hear from you.

Write to us here for feedback on The Intersection.