Good morning! India has tried many ways to produce clean-burning fuel to run vehicles and light up homes. Husk power was once touted as the next big thing in clean energy. Brazil’s success with fuel doping encouraged India to adopt ethanol. But the country is yet to find a way to produce biofuel at scale. Another Latin American import—a prickly cactus—is the government’s new hope. Roshni P. Nair explores its possibilities. We have also handpicked a list of weekend reads for you.

Miguel Urieta/Unsplash.com

The people of Kutch, Gujarat, have had an unwanted guest in their midst for over half a century. Its name is prosopis juliflora but locals call it gando baval, which literally translates to “mad tree”.

It was introduced to India by the British, but propagated by the state government in the 1960s to halt the spread of salt marshes. The mad tree did more than was expected of it. It conquered the ecologically-sensitive Banni grasslands and got labelled as a noxious pest. But gando baval is on the road to redemption. Researchers are discovering that it gives as much as it takes, from creating a local charcoal economy to being a potential source of food and brandy.

Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have Australia tumma or “Australian acacia”. It’s also called sarkar tumma because in this case too, it was the government that propagated the seeds (from airplanes no less) in the 1960s. The objective was to green the land, and for India to become self-sufficient in tannin, the organic substance that’s derived from acacia and used to preserve leather. But sarkar tumma—like gando baval, eucalyptus, lantana camara, and other vilayati or foreign “invasives” that made India home—refused to conform to human expectations. It ran amok.

The hope is that opuntia ficus indica will be different.

Better known as the cactus pear or prickly pear, opuntia ficus indica may not actually be vilayati. It’s supposedly native to the Americas but some academics think it may have spawned from India. Suffice to say, it’s a complicated plant: it’s as content in a tiny pot as it is in unforgiving, barren landscapes, occupying the grey zone of being ‘invasive’, but not reviled.

The wild cactus pear has spines and is therefore unpopular with both humans and animals. The cultivated version isn’t thorny, which is why the Indian government wants to harvest it for food and biofuel. The 2023-24 Union Budget may have a roadmap for cactus cultivation. Until then, rural development minister Giriraj Singh is amping up efforts to promote growth and adoption.

A who’s who of scientific institutions—such as the Indian Council of Agricultural Research and the Central Arid Zone Research Institute, to name just two—have trained their sights on opuntia-everything for over a decade now. Even the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, and the NGO BAIF Development Research Foundation, are involved. The tie binding all these participants is an autonomous, global non-profit called the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Land Areas (ICARDA).

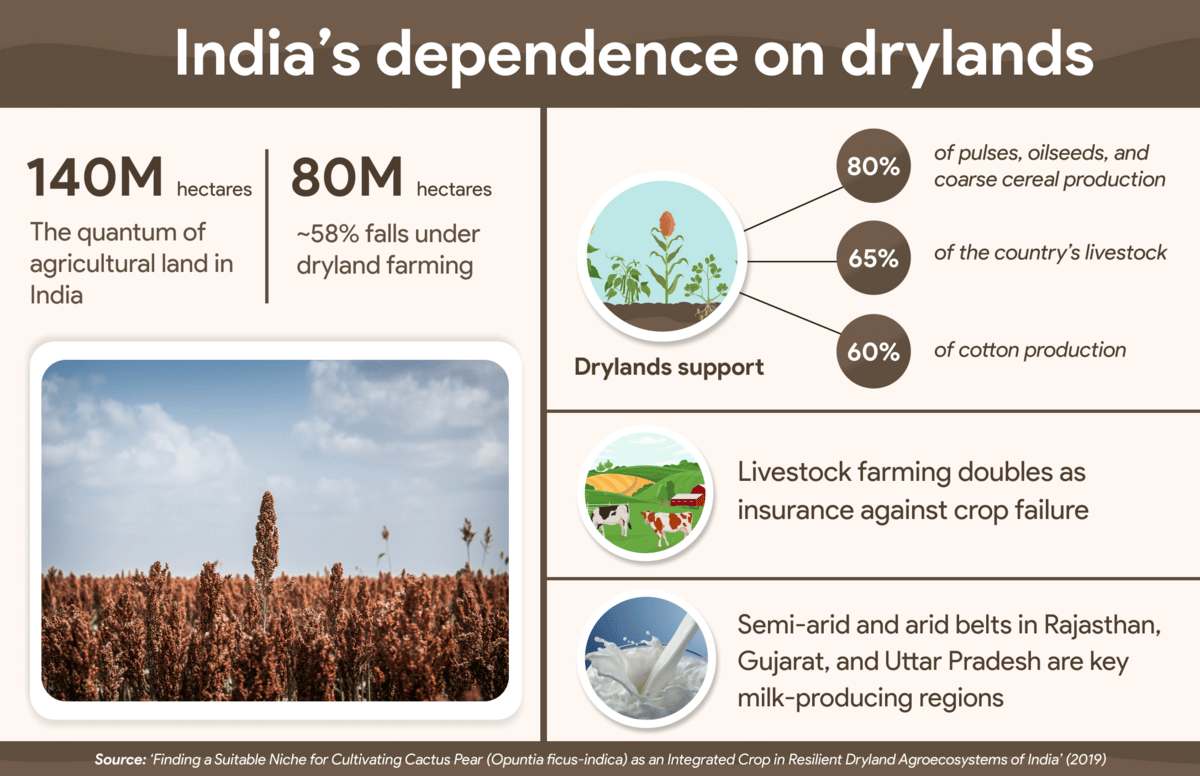

The Centre believes the cactus pear may also “restore” degraded land and reduce dependence on rain-fed crops in the drylands, since monsoon is becoming unpredictable due to climate change. ‘Dryland’ is an umbrella term for regions characterised by water scarcity.

Graphic by Harish Arjun Suresh

This is all to say that the cactus pear could be India’s next wonder crop. It’s drought-resistant, low maintenance, and has great livestock feed and biogas potential.

What could go wrong?

Creating something out of nothing

If this seems like a story about agriculture, it isn’t. All those years of research will be in vain if there’s no product-market fit. That term is a cliché thanks to the startup ecosystem, but it’s (sadly?) relevant even in a world desperate for climate-resilient solutions.

Mexico has a storied tradition of cactus pear consumption. The crimson fruit is pulped to make jams, jellies, and an alcoholic drink called colonche. The plant itself is grilled, included in salads and tacos, even turned into huevos con nopales, or eggs with cactus. Which is why farmers grow it, retailers stock it, and everyone else turns it into biogas. South Americans aren’t as big on nopal or cactus except for animal feed and folk medicine, but even that’s enough for biogas enterprises to crop up in Brazil and Chile.

Barring the example of cactus fruit juice or hathla thor nu juice, as it’s known in Saurashtra, Gujarat, Indians don’t care for the humble cactus pear. The only remotely-spiky thing we’re enthusiastic about is aloe vera, and it’s not even a cactus. It’s a succulent. You can argue that one can create a market from scratch by manufacturing a want (looking at you, ultrafast delivery); but that’s a luxury afforded by cash-burning businesses, not farmers in drought-prone regions.

“Even if something ticks the right boxes, farmers won’t grow it if there aren’t buyers for it,” Sri Krishna Sudheer Patoju tells The Intersection. Patoju is assistant professor at the Tuljapur Campus, School of Rural Development, Tata Institute Of Social Sciences.

“Any market orientation [for cactus] may need to focus on a health and wellness push, or rely on a robust public distribution system. It was public distribution that turned India into a bigger consumer of rice than ever before.”

GV Ramanjaneyulu concurs and goes a step further. The executive director of the Centre for Sustainable Agriculture (CSA) adds that cactus pear attracts cochineal insects, which produce carmine. This red pigment has been used as natural colouring in the Americas for thousands of years, which is well and good, but…

“Cochineals are mealybugs. And mealybugs are pests. Whether or not they can destroy nearby crops [such as millets or pulses] needs to be looked into,” he says.

Yes, cochineals already exist in the wild, since cactus pears do too. But monoculture farming is a different beast. Pests love plantations. Because of this inevitability, farmers’ land, labour, and maintenance costs will go up— all while they wait for the plant to bear fruit in anywhere between one and four years, and find buyers for it… if they’re lucky.

Tl;dr: both Patoju and Ramanjaneyulu think the cactus pear holds promise. They also think it needs to be made economically viable, stat.

The B word

In December 2022, India held a meeting with the ambassadors of Mexico, Morocco, Brazil, and Chile over the cactus pear. Also in the meeting were scientists from India, Tunisia, Italy, and South Africa. Mounir Louhaichi was one of them.

Louhaichi, based in Tunisia and associated with ICARDA, has shepherded Indian cactus pear research over the last few years. Over a Zoom call with The Intersection and Sawsan Hassan, also of ICARDA, he recounts the time a Rajasthani farmer treated the cactus like poison. The year was 2017, and researchers were surveying smallholder farmers to figure out what they thought of the plant.

“We were handing out cactus pads. This one didn’t trust us. He chose to eat it himself before giving it to his animals,” Louhaichi recalls. Fast forward five years, he says, farmers have warmed up to the idea of growing cactus near their homes.

Louhaichi, Hassan, and the Indian cactus consortium, if one can call it that, stumbled on some interesting findings. Such as the fact that the cactus pear stores more starch when there’s less soil volume. That a cactus planted in July is taller and fatter than a cactus planted in October, but not as nutritious as one planted in February and April. That Rajasthan, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Odisha are most conducive for the plant, while the dry pockets of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra aren’t. They also pinpointed which accessions or cultivars will excel in Indian conditions.

If this bores you, know that agri science underpins the food and commodities chain (and by extension, the gut and the global economy, respectively). The outcomes of such research shape the market for produce and inevitably dictate why you consume more Kinnow than Nagpur oranges, or why your Nashik grapes taste different than they did a year ago. Let’s just say a sh*t ton of science went into farming the aloe whose gel you apply on your face, and the staples you buy from your neighbourhood vendor or BigBasket. And it’s science that will lay the foundation for cactus cultivation here.

Science will also optimise the cactus pear for biogas. And this is where people like Mounir Louhaichi and Sawsan Hassan are key. Their research up until this point established the basics. They now have to determine what will fatten the chicken, so to speak. As Louhaichi says:

“The purpose of the previous map was to illustrate where cactus can be cultivated. Now our objective is different as we need to provide the cactus with favourable conditions to extract maximum potential.”

This matters because as one mentioned above, the Indian government also wants to use cactus pear as biogas. It’s barely talked about, but we have a National Policy On Biofuels. This policy, like the better-known climate or Net Zero targets, has a deadline. India wants to achieve 20% ethanol blending rates by 2025-2026 (pdf), and 5% biodiesel blending rates by 2030.

Ethanol is derived from the water-guzzling sugarcane and comes with its own set of problems. Ditto biodiesel, which mostly uses vegetable oils— including soybean and palm oil, whose cultivation is as environmentally-friendly as Satan is god-fearing. Because of these headaches, India tried to make jatropha, the wild shrub known as ratanjot, a biodiesel success story. It failed spectacularly because of poor seed yield, and because our biofuel ecosystem is both economically and environmentally unsustainable.

This track record doesn't deter Rodrigo Wayland Morales, although he admits that “cactus is not in the Indian culture”. Morales is founder of Elqui Global Energy, a Chilean company that offers turnkey solutions to make biogas out of the cactus pear. Morales last visited India in November 2022 and claims to have had a fruitful trip. But he isn’t revealing anything (“My clients are confidential… [but] soon we will have important news”).

“In energy equivalent terms, cactus biogas produces 12,000 litres of diesel per acre per year. It’s feasible to produce 1,000 tons of biomass per hectare [or 2.2 acres],” he tells The Intersection. “If a small farmer works in a cooperative system where he delivers the cactus to a plant for processing, he can earn $2,000 [₹1.6 lakh] per hectare per year. That’s enough to change the life of a farmer who has two-three hectares.”

This sounds great until you remember that the cactus pear in India has been relegated to hathla thor nu juice. It’s early days, yes, and the lot more that needs to be done will probably be done. But one remembers what else CSA’s GV Ramanjaneyulu and Mounir Louhaichi warned about: pests are a serious concern, and cacti shouldn’t be expected to rejuvenate degraded lands.

They say the cactus pear tastes like green beans. If nothing else, it will at least be more appetising than gando baval.

ICYMI

Shifting blues: The world’s most valuable company, Apple, also has arguably the most efficient global supply chain. That much of it exists in China, its home country’s biggest geopolitical and trade rival, is testimony to the company’s ingenuity and CEO Tim Cook’s leadership chops. If Steve Jobs obsessed over every curve and notch of Apple gadgets, Tim Cook was consumed with perfecting each link in its global supply chain.

In a two-part series, Financial Times looks at how Cook oversaw the building of Apple’s China base, micro-managing everything from location to equipment and how the company is now finding it difficult to loosen its ties to the country.

Apple helped create an ecosystem in China, complete with a highly trained army of workers and sophisticated equipment. While 426,716 Chinese organisations had a high level of quality certification in 2021, India had 36,505 and the US, just 25,561. Yet, Apple has to find new locations to reduce its dependence on China not only to reduce risk, but also because it is not as much in control over equipment and processes as it was a decade ago.

Bearers of history: Its very name is used as a term of disparagement. But the humble donkey was key to shaping human history for millennia. Modern day donkeys and mules are descendants of the African wild, one of the earliest animals to be domesticated. Their extraordinary capacity to carry enormous burdens for long distances made them prized possessions throughout history, especially for traders and armies. Recent archaeological digs in a village near Paris have unearthed evidence of giant donkeys. Researchers say that they were bred by Romans and were so gigantic that they would dwarf horses. BBC has a fascinating story on the big-eared beasts of burden.

Finland versus fake news: For five years in a row, Finland has topped the Open Society Institute’s survey of European countries most resistant to misinformation. The New York Times set out to find what the Nordic country does right that others don’t, and found the answer in its education system. Media literacy is part of the core curriculum since preschool. It also helps that Finland’s public education system is one of the best in the world, meaning teachers have the time and resources to help students spot differences between news in traditional media and news on social media. A fitting reminder that teachers need far more support than they get elsewhere.

Uncovering An Online Secret: If you enjoy investigative podcasts, check out Can I Tell You A Secret? by The Guardian. This six-part series delves into the case of serial cyberstalker Matthew Hardy. Guardian journalist Sirin Kale, the host of this series, investigates each aspect of the crime and reveals what actually transpired with the victims. Much like the popular TV show Mindhunter, this podcast dives head-first into criminal psychology, and answers the why, rather than the what and how.

Tube talk: Indian YouTube influencers are changing the fortunes of small businesses in Chandni Chowk, Delhi. Ask Mohammad Ali, who saw an uptick in sales after a Delhi-based influencer made a video about his shop. Ali then had to rent a bigger space to accommodate customers. Several small stores peppered across one of India's biggest markets are now benefiting from the viral views spurred by the desi content engine. How so, you wonder? Because direct customer walk-ins result in more moolah for old-school retailers than selling on Flipkart and Amazon.

Is the plant-based industry wilting? There was a time fake meat companies were poised to take on the world’s $1 trillion meat industry. Impossible Foods, for instance, raised $183 million before it even sold a burger. At one point, McDonald's, KFC, Nestle and even Tyson Foods, the world's largest poultry producer, gave in to FOMO. Circumstances have become anti-climatic since then. Plant-based meat, which gained momentum during the pandemic, is reduced to a buzzword today. Shares of most companies in this space have come back to earth. This story in Bloomberg explores why this happened.