Peeling the layers off the Indian skincare boom

Consumerism is one thing. Science is another. Do the twain meet?

Good morning! Do you have a skincare routine? Whether yes or no, today’s story is for you. A burgeoning market in India for single-ingredient focused products—products that have hyaluronic acid, Vitamin C, niacinamide, retinol, or other “actives”—has turned chemistry into commerce, commerce into art, and skincare into self-care. Companies operating in this space typically use science to validate their claims. How does that hold up?

If you enjoy reading us, why not give us a follow at @thesignaldotco on Twitter and Instagram.

We are all Cleopatra. Those of us who swear by chemical peels, anyway. Legend and a peer-reviewed paper in JAMA Dermatology tells us that the Egyptian queen, whose life puts every Game Of Thrones story arc to shame, bathed in sour milk. People argue over whether this milk came from goats, donkeys, or both, but that’s not the point. The point is that Cleopatra indulged in chemical peeling, a form of exfoliation that removes dead cells and gunk from the uppermost layer of the skin.

Sour milk contains lactic acid. Circa 2023, lactic acid is one of many “actives”—hero ingredients that target specific concerns—eulogised in modern skincare. By modern skincare, we mean an industry that’s turned consumers into cosmetic chemists, and anyone even remotely famous into a wannabe dermatologist.

‘Skinfluencer’ Hyram, who has 4.5 million YouTube subscribers, founded Selfless. Brad Pitt, the superstar rumoured to be super smelly, has an obscenely-priced genderless skincare range called Le Domaine. Kim Kardashian, Scarlett Johansson, Blink-182 drummer Travis Barker, Hailey Bieber, unpopular Joker Jared Leto, and innumerable others have skincare lines too. Closer home, Deepika Padukone has 82°E and Anusha Dandekar has Brown Skin Beauty. Alia Bhatt has no such thing, though she may as well: her latest skincare routine video, in which she and sister Shaheen namedropped glazing fluids, face mists, lip treatments, etc., has 2.2 million views.

To be fair, this lot didn’t fuel the craze. They’re just cashing in. What began with the 10-step Korean skincare routine and a clamour for “glass skin” reached an inflection point after 2016, the year Canadian company DECIEM launched its skincare brand, The Ordinary (TO). TO’s appeal lay in its affordable, no-nonsense products. Instead of labels like ‘organic’ or product categories such as ampoules and eye creams, the brand marketed its use of actives. Niacinamide, retinol, ceramides, squalene, peptides, Vitamin C, hyaluronic acid, AHA-BHAs (alpha hydroxy acids and beta hydroxy acids), and other compounds became unique selling propositions. Some of these were longtime staples in prescription dermatology products. But TO turned chemistry into an aesthetic—to the point where you’d feel basic for not educating yourself about skincare formulations.

The outcome is a monomania for the largest human organ. The Indian skincare industry, worth $6.5 billion in 2022, is projected to touch $8.8 billion by 2027. TO-inspired labels such as Minimalist, Earth Rhythm, Juicy Chemistry, and Suganda have spread like a rash. Honasa Consumer Ltd, the parent company of Mamaearth, has a house of skincare brands comprising Dr Sheth’s, The Derma Co, Aqualogica, and Ayuga. BOLD, the venture arm of L’Oréal that has a stake in Mamaearth investor Fireside Ventures, recently invested in venture capital fund DSG Consumer Partners. DSG has stakes in Deepika Padukone’s 82°E and three other personal care brands. And FMCG biggie Unilever is an investor in Minimalist, via Unilever Ventures.

Homegrown hype over ‘skincare science’ is real. But is it justified?

The answer is more convoluted than both naysayers and consumerists would have you believe.

Testing, testing

For Jaspreet Gulati, what began in 2017 will finally culminate into a market-ready product in July 2023.

Gulati is the co-founder of Chandigarh-based Hitech Formulations, an offshoot of Lyra Laboratories, a clinical dermatology lab headquartered in Solan, Himachal Pradesh. Hitech has created 1,546 formulations for clients such as Cipla, Re’equil, Dot & Key, Honasa Consumer Ltd, Zydus, and Mankind. In other words, Gulati’s clients span the spectrum from the heavily-regulated pharma to the lightly-regulated personal care sectors. Two of Hitech’s creations have achieved cult status in India: UV Doux’s Silicone sunscreen, and Re’equil’s Ultra Matte Dry Touch sunscreen.

“Of the 100 or so brands in the market, 99% are marketed formulations developed by someone else.”

—Saurabh Arora, MD, Auriga Research

Gulati won’t name the anti-acne product that’s taken him six years to formulate, for a brand that also remains unnamed. But he lays bare the regulatory grey zone for ‘dermaceutical’ products—the ones with clinical prefixes and suffixes that promise dewy skin, if not more.

“Just because something is stable or doesn’t have heavy metals, doesn’t mean it’s safe,” he says.

The context to his statement are the Cosmetics Rules, 2020 (pdf), which is under the purview of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), India’s drug regulator. These codify how cosmetics or their ingredients should be licensed, tested, inspected, and manufactured. The Rules also say that end products must be tested in accordance with IS 4011:2018. That’s code for ‘Methods of Test for Safety Evaluation of Cosmetics’, established by the Bureau of Indian Standards. IS 4011:2018 has directives on the minimum number of adult human subjects (24) and measuring adverse reactions. Together, the Cosmetics Rules, 2020 and IS 4011:2018 prohibit animal testing and heavy metals, and mandate safety testing.

They do not establish standards for efficacy.

This is what Jaspreet Gulati alludes to. Because everyone is desperate to differentiate, niacinamide concentrations have gone from 5% to 15%, Vitamin C concentrations have reached 25%, and ingredient lists have morphed into the longest epic. The quest to market effectiveness could leech into safety. Brands are tooting science for the sake of commerce, citing “clinical trials” to validate claims of skin brightening, hydration, anti-ageing, and so on. Read their fine print though, and you realise the “trials” are consumer studies drawing on subjective feedback. As Dr Mira Desai tells The Intersection: “This indicates that brands don’t have robust evidence before marketing. Evidence is generated only by randomised or double-blind studies. If you check our reference textbooks, there’s very little to show that such ingredients have an actual effect.” Desai is the former professor and head of pharmacology at BJ Medical College, Ahmedabad, and an expert on research ethics and clinical trials.

“These products claim to do more than what I promise my patients even with a gold standard laser.”

—Dr Punit Saraogi, dermatologist

Of course, the counter is that Indian regulations don’t mandate pharma-grade testing for cosmetics. So brands aren’t obligated to prove anything other than the fact that their formulations are stable and won’t dissolve your face. But here too, not everyone pulls their weight.

“If you’re using ingredients in your product that have a likelihood of an allergic reaction, your study should ideally be done over 3-4 months or longer,” says Malika Sadani, founder-CEO of The Mom’s Co and an investor in personal care brands. “But this is not mandated, so it’s up to the brand’s discretion.”

Efficacy testing also isn’t a priority because of costs. Sadani adds that a consumer study conducted by a third party agency costs ~₹2 lakh per stock keeping unit (SKU); a clinical one costs up to ₹10 lakh. These numbers fluctuate depending on what’s being tested, which lab a company chooses for testing, and whether the test is in vivo (performed on live subjects) or in vitro (performed on samples collected from live subjects). Juicy Chemistry founder Pritesh Asher says clinical studies for the skin range anywhere between ₹5 lakh-₹10 lakh per SKU, while those for hair cost ₹15 lakh-₹20 lakh. Mohit Yadav, co-founder of Minimalist, tells The Intersection that in-vitro testing for a product sets one back by ₹15,000-20,000 per SKU. An in vivo one can go up to ₹5 lakh.

And here’s a fun fact: results from in vivo and in vitro testing can be chalk and cheese for the same product. According to Yadav, the regulatory framework deems that in vitro studies are enough to establish the Sun Protection Factor (SPF) of a sunscreen. But:

“All our sunscreen products were tested in vitro. One lab gave our Invisible Sunscreen a value of 80 SPF. Another gave it 60 SPF. We could’ve just taken the average of those values, but didn’t,” he shares. “We did in vivo testing and got a precise value.”

If efficacy testing for skincare products is the Wild West, the science of actives is the Mad Max wasteland.

Science itself

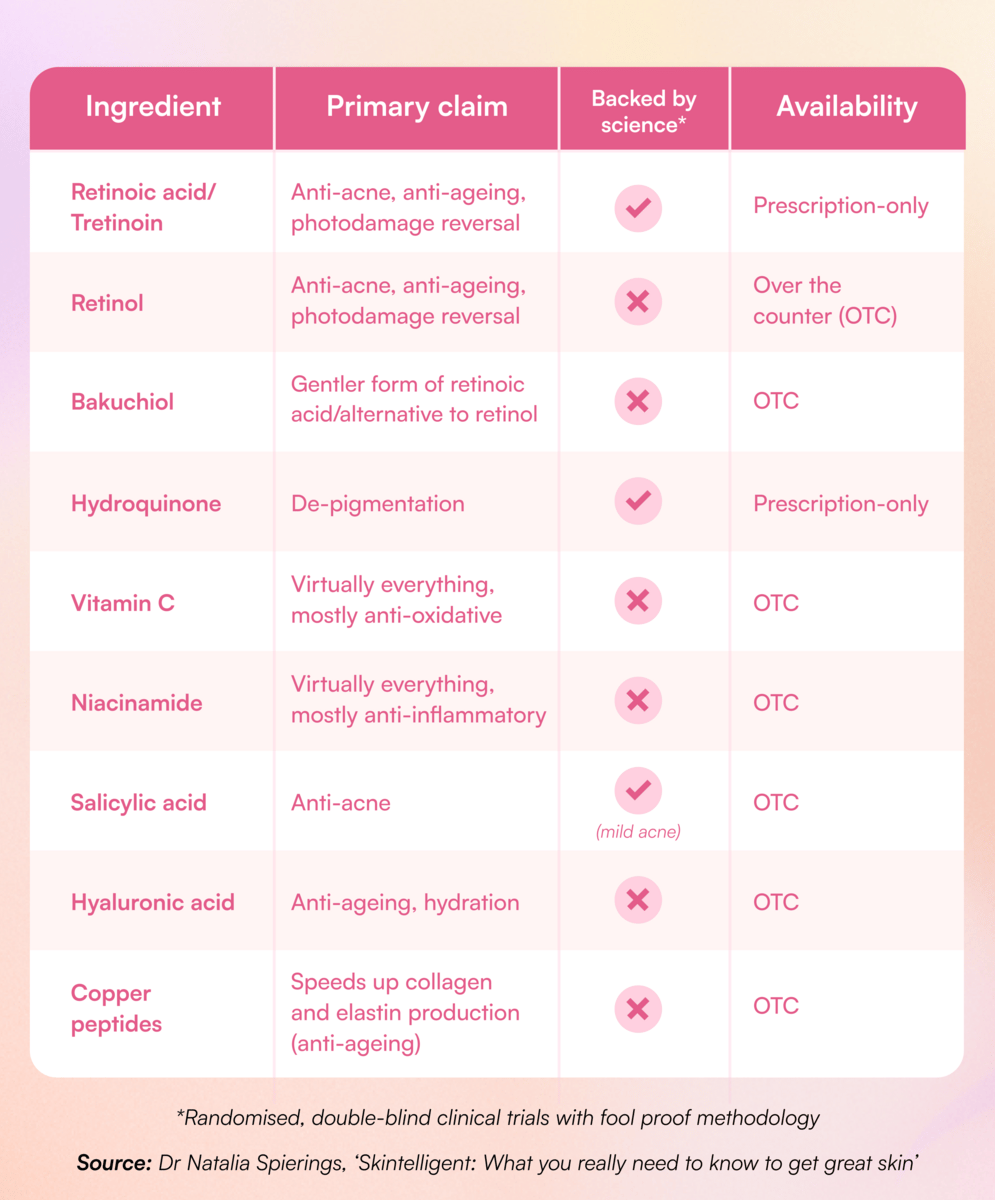

UK-based dermatologist Dr Natalia Spierings’ Skintelligent: What you really need to know to get great skin will make you feel either stupid or angry. That’s a good thing. In writing about how the skin works at the cellular level, and why modern skincare is (spoiler alert) largely trash, Spierings also reveals that the scientific community is to blame. By which we mean that even the most famously “science-backed” actives, such as niacinamide, aren’t backed by squeaky clean science. According to Spierings, all positive studies for niacinamide “either have major methodological or statistical analysis flaws or are industry-sponsored or both”.

Graphic by Harish Arjun Suresh

This is a raw deal for an organ that is our sensory gateway to the world, makes up 15% of our weight, and keeps our insides inside. Is it because skincare is associated with vanity, or because dermatology itself isn’t accorded the same respect as other medical disciplines? We’ll never know. What we do know is that some of the world’s biggest chemical and biotech companies, such as BASF, Clariant, Givaudan, Ashland, Lonza, etc., supply a bulk of the actives and have huge research and development teams.

If there’s scientific opacity about actives—the beating heart of modern skincare—there’s bound to be scientific opacity about formulations and products.

Take hyaluronic acid (HA), a current darling that’s getting called out for being scammy. Spierings thinks its hogwash too, because its molecular weight is 4,000-8,000,000 dalton—way too huge to go deeper than the stratum corneum (the uppermost layer of the skin) and have any anti-ageing benefits.

“Its holy grail status is disappointing. At best, HA improves the feel of the product and offers service level moisturisation,” agrees Mumbai-based dermatologist Dr Rickson Pereira.

But Jaspreet Gulati of Hitech Formulations reckons that the “Pandora’s box” HA molecule can be broken down. The more you chip away at it, the more likely it may be to go deeper into the epidermis, he claims. This is why actives with small molecules typically come in low concentrations; salicylic acid at 2%, for example.

Then there’s topical Vitamin C, which comes in numerous forms. L-Ascorbic Acid (LAA) is the purest, but it’s notoriously unstable, making it a no-go in Indian conditions. Not everyone gets it though.

“Too many companies want to launch without understanding all this, and things like bioavailability. I have to school them every time. They just want more ingredients or higher concentrations. In their haste, they don’t spend time on design,” Gulati tells The Intersection.

The question mark over some actives and brands’ tendency to cosplay as alchemists (rather than learn basic chemistry) is compounded by the fact that there’s no consensus among dermatologists either. Take this 2016 paper published in the Indian Journal of Dermatology, which says there’s little to show how moisturisers work on Indian skin. So much for the mantra ‘cleanse, moisturise, and use sunscreen’. Then there's this article, which says no one knows what causes acne. And this, the only randomised, double-blind study on bakuchiol—which Dr Natalia Spierings faults for its methodology.

In essence, over the counter skincare is personal and shouldn’t be marketed as an absolute science. After all:

“Any brand can upload literature or information on a product listing that sounds scientific enough,” says Shankar Prasad, founder and CEO of Plum Goodness. “I don’t think the average person can tell the difference between something scientific, verifiable, and all the rest.”

If we were to leave you with a takeaway, it would be this sage advice that contradicts everything the cosmetics industry has told you over the past few years. It comes from the former president of the Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists. Dr Rashmi Sarkar is also founder-president of the Indian Women's Dermatologic Association.

“The best products are the ones you can afford. Even coconut oil is a good moisturiser, though it’s not aesthetically pleasing or suitable for everyone. For cleansing, soap is fine as long as it’s mild,” she says. “Calamine is good. And you don’t need to avoid something because it has mineral oil or silicone in it, as long as it’s medical grade. Just look out for dyes, heavy fragrances, and colouring agents.”

Don’t expect too much, and don’t overdo it. You see, even Cleopatra didn’t.

Note: An earlier version of this story misspelt Malika Sadani’s name. We regret the error.

ICYMI

The King’s new shoes: In 1984, a young basketball player named Michael Jordan chose to sign an endorsement deal with Nike over his earlier preferred Adidas—a decision that would change the sneaker and sports marketing industry forever. You probably already knew that story. But did you know that about two decades later, an 18-year-old basketball player became one of the richest athletes in the world even before playing his first NBA game? That player was LeBron James. Check out this excerpt in Esquire from Sports Illustrated writer Jeff Benedict’s new book, LeBron, about a three-way battle between Reebok, Adidas, and Nike for the King's first sneaker deal.

Mismatched: The old saying that beauty is in the eyes of the beholder is also true of value. The value of anything is based on perception and, to some extent, intent. In this fascinating account of Buzzfeed founder Jonah Peretti breaking off his company’s proposed sale to Bob Iger’s Disney, which would have resulted in a record-breaking $600 million media deal, Ben Smith, the editor of the popular website at the time, draws out the value mismatch. While Peretti, who valued independence and freedom above all else, saw Buzzfeed getting lost in the corporate culture of Disney, his colleagues and Iger saw his rejection as foolish and value-destroying. While Buzzfeed retained its freedom to rewrite the rules of the media industry and sold shares to the public instead of a media giant, Peretti’s bet on the perennial rise of social media was misplaced. And Iger, who said that Buzzfeed would never be valued—in monetary terms—as much as it would have had it stayed with Disney, was proven right.

Shiny Happy People Once a society survives a pandemic, it lets go of cynicism. Or at least that’s what has happened to the youngest of us. This RollingStone story documents how Gen-Z has turned the internet from a jaded, ironic hellhole into a safe space for earnest, “cringe” conversations. For millennials, being cringe online was anathema; but for the younger lot, social media was the only outlet left to be vulnerable and truly connect with their loved ones, especially when successive lockdowns had separated family and friends. This generational shift may change what the young consider “cool”. Being carefree is no longer the “in”; the young are all about dedicating themselves to a cause. Is the internet getting… more wholesome? We’re tearing up.

Love at first swipe: Dating apps have changed how we find love. First came the personality quizzes on OkCupid. Then, the swipe era made popular by Tinder ushered in a design concept that finds relevance to this day. The feature was such a hit that Bumble still uses it, and it went mainstream with Instagram. Hinge struck gold with its Voice Prompt feature, which went viral on Instagram and TikTok, and gave other dating apps enough reason to do a copypasta. What unites everyone, though, is the common ick for Roses on Hinge. It's Nice That details how the need to gamify dating apps brought about design features that quietly changed how we communicate on a daily basis.

Free fall: Back in 2019, Beyond Meat was Wall Street's favourite stock. Today, the plant-based meat company is still trying to find a way to warm up to omnivores. In fact, a capital infusion is likely needed to save the company from potential bankruptcy. So, what went wrong? Price disparity was one reason why plant-based meat consumption didn't last longer than a hot minute. High-income households haven't quite developed an appetite for the meat substitute. Canada-based Maple Leaf Foods posted a loss of $191 million in November 2022 from its plant protein arm. As a result, while the global plant-based category is worth $28 billion, non-dairy substitutes are earning some $$$. The Financial Times points out what's ailing the once-hallowed brand.

Succession, again: Succession is in the air. And spoilers aside, this isn't about Logan Roy or Rupert Murdoch, but Michael Bloomberg—the man who founded, well, Bloomberg. Now 81, Bloomberg, to quote the Financial Times, is contemplating life without its eponymous founder. Bloomberg is likely to transfer his company to Bloomberg Philanthropies. But that's just one part of the story here. The piece delves deeper into Bloomberg and how he built a financial data empire with a terminal at the heart of it.

Good