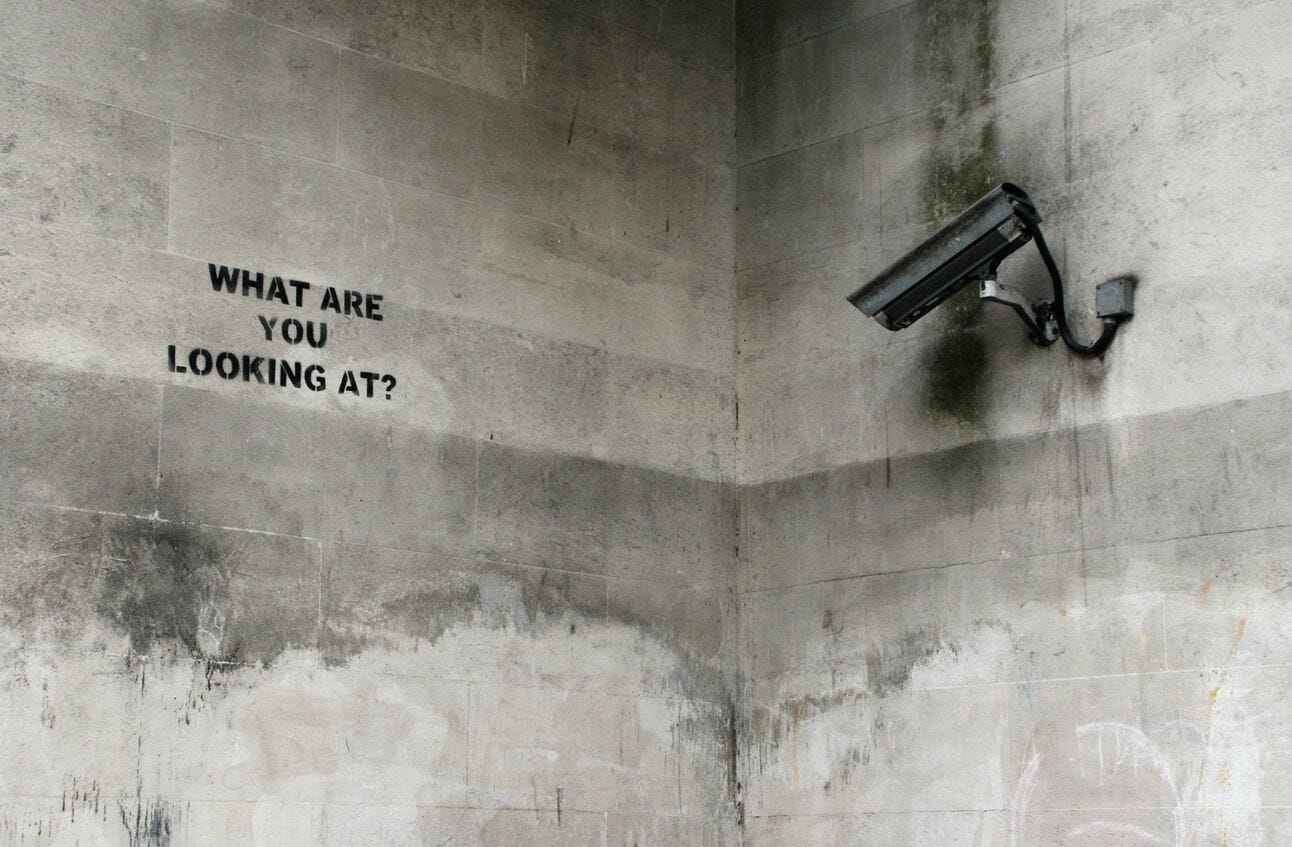

Unmasking Banksy

Good morning! For over two decades, the world—journalists, internet sleuths, and litigious companies included—has wracked its hive mind trying to figure out who Banksy is. The world’s most famous street artist and raconteur, who’s inspired copycats from Mumbai to Miami, is worth anywhere between $20-50 million depending on where you look. Thing is, Banksy’s brand value and pop culture influence hinges entirely on his anonymity. That anonymity may now go poof because of an impending defamation case. Though speculation is rife that Banksy is a Bristol-based guy named Robin Gunningham, it’s never been confirmed. What’s more, there’s a theory that Banksy isn’t one individual, but a collective that functions like a mainstream brand and fiercely guards its copyright. Check out today’s story from The Conversation about the tea on Banksy’s “street cred”. Plus: a curated list of the week’s best longreads.

The Signal is on Telegram! We've launched a group — The Signal Forum — where we share what we’re reading and listening through the day. Join us to be a part of the conversation!

If you enjoy reading us, why not give us a follow at @thesignaldotco on Twitter, Instagram, and Threads.

Photo credit: Niv Singer/Unsplash

The graffiti artist known as Banksy might be unmasked in an upcoming defamation case over his use of Instagram to invite shoplifters to go to a Guess store because it had used his imagery without permission. The case could be seen as an attempt to force Banksy to relinquish his anonymity, which, many say, has been important to his success over the years.

There has been much speculation as to the identity of the artist and he is believed by many to be Bristol’s Robin Gunningham, who was named as a co-defendant in the defamation suit. While it has not been confirmed that Banksy is Gunningham, pointing this out is in no way a revelation. Moreover, trying to find out Banksy’s identity ultimately does not matter.

There have been many investigations into the artist’s identity and it has been the topic of serious journalistic and academic investigation for years, but no one has been able to absolutely link Gunningham and Banksy.

Short of Gunningham’s admission, complete certainty is unlikely. But if Banksy’s identity is revealed, police forces around the world could bring vandalism, property destruction, criminal mischief or worse charges against the individual.

Gunningham revealing himself would also destroy the Banksy mystique.

He is not likely to snitch on himself or damage the brand. The more important reason Gunningham being Banksy doesn’t matter is because there is no Banksy – no individual who is Banksy anyway.

A collective

At one time, there was one Banksy who had a graffiti career and a famous “beef” in the subculture with London graffiti legend Robbo. That time is gone.

Banksy is now a collective of artists who work together to produce thoughtful, provocative and subversive pieces and installations. The scope and secrecy of Banksy’s larger works require the cooperation of many individuals to orchestrate, direct and produce them. The “bemusement park” Dismaland (a sinister take on Disneyland-style theme parks), the Walled Off Hotel (Banksy’s hotel and commentary on the Israel/Palestine conflict) in Palestine and Better Out Than In (Banksy’s New York-wide art residence) are examples of this.

Investigators believe that the collective includes many well-known and established artists. Bristol street artist John D’oh is among those rumoured to be involved, as is graffiti and street artist James AME72 Ame and perhaps even Massive Attack singer Robert Del Naja, among others. This is speculation. And again, this doesn’t matter.

What matters is why Banksy has been in the courts recently. More important than the current defamation suit is the 2021 rejection of Banksy’s trademark by the EU. This was the result of Banksy’s battle with street art greeting card producer Full Colour Black, who used Banksy’s image of a Monkey wearing a placard without permission. The ruling uses Banksy’s own words in the decision, stating:

The ruling notes that the street artist explicitly stated that the public is morally and legally free to reproduce, amend and otherwise use any copyright works forced upon them by third parties.

Also, “copyright is for losers”, as Banksy said in his own 2017 book, Wall and Piece.

The application to declare the trademark invalid was filed in 2018. Banksy took great umbrage at this. In October of 2019, he officially revealed the “homewares” brand Gross Domestic Product. The store is officially the website, but it debuted as a pop-up shop which couldn’t be entered.

A statement posted on the pop-up “storefront” declared that Gross Domestic Product was opened in direct response to the trademark cancellation filing and that selling Banksy “branded merchandise” was the best way to ensure ownership and control of the Banksy name. What’s important here is the clear interest in wanting to maintain control over what is and is not a Banksy and what Banksy artwork is associated with in commercial spaces.

A team of professionals

Banksy fakes are everywhere. The artist’s popularity and the fact that the bulk of Banksy’s work is stencils – which are easily reproduced by anyone with some talent, time and an Exacto knife – ensure fakes and copies will continue to be made. To combat this, Banksy has a cohort of trusted art dealers for official Banksys and an authentication service called Pest Control that chases and legitimates the provenance of Banksys.

While it is entirely legitimate for any artist to want to maintain their unique identity and control over their artwork, it’s rare for an artist to maintain an entire staffed department dedicated to it. Not that graffiti writers don’t defend their copyrights.

Revok, Futura and Rime (to name a few) have defended their ownership of their graffiti and art in court. They hired lawyers, but they didn’t have a division dedicated to preempting and preventing infringement.

Pest Control is seemingly in place to maintain the authentic and unique perspective of Banksy’s works and to confirm they were officially produced by Banksy. This is a process often referred to as brand maintenance.

So, what’s the point of all this? Well, Banksy was an individual street artist at one point. This was probably Robin Gunningham. However, Banksy is now a collective of artists who work under the Banksy brand to produce the works that the Banksy authentication service, Pest Control, officially decrees as Banksys. Banksy is also a team of lawyers, art dealers and curators who ensure that only works officially associated with the Banksy brand get the certified Banksy seal of approval.

None of this is secret, but it’s not been publicised because being a litigious art collective equally as dedicated to producing art as engaging in brand maintenance doesn’t evoke the solo, clandestine, provocative raconteur image Banksy is going for. Having a team of lawyers making sure only real Banksys are labelled as such doesn’t do much for your street cred. Still, revealing this publicly likely won’t diminish interest in Banksy or affect the price people are willing to pay for monkey stencils or self-destroying art.

Tyson Mitman is Senior Lecturer in Sociology and Criminology, York St John University.

This article is republished from https://theconversation.com under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article at https://theconversation.com/unmasking-banksy-the-street-artist-is-not-one-man-but-a-whole-brand-of-people-215293

TECHTONIC SHIFT

Would you pay to use social media?: Ad-free subs on the likes of Snap aren’t new. But as the EU clamps down on targeted ads, Meta—the company that set the very template for ad-monetised social media—is introducing paid versions for the continent. Ad-free Instagram and Meta may cost $14-17 a month, depending on the package. TikTok is also piloting a subscription version. This begs the question: would users, especially Gen Z and younger, pay for the stuff? In this week’s episode of TechTonic Shift, Rajneil and Roshni discuss social media fatigue and platforms’ diminishing returns. Available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music, or wherever you get your podcasts.

ICYMI

A new dream: BTS ARMY, this one’s for you. With the world’s biggest boy band on hiatus for at least two years due to mandatory military service, the man who got them together wants to do it all over again, but with a slight twist. South Korean music mogul Bang Si-Hyuk recently unveiled his new project called The Debut: Dream Academy. Over the last two years, Bang and his deputies sorted through over 120,000 applications to form a new girl group. The current shortlist is 20 women aged between 14 and 21, from a dozen different countries. The new group, whose final count hasn’t been announced yet, will be US-based and perform in English, not Korean. If it succeeds, he’s got big global plans. As the Dream Academy gets into shape, read all about how Bang is building the next BTS in this Bloomberg Businessweek story.

Why we are culturally bankrupt: Almost all of us have pondered over one of the stickiest questions of our time: why is contemporary culture a rehash or regurgitation of the past? Why is technology bereft of innovation, music bereft of originality, and fashion bereft of anything other than circa-1990s high-waist jeans and aughts-coded ballet flats? The New York Times critic at large Jason Farago has the answer. Farago accurately identifies and ruminates on the contradictions (for one: infinite scrolling, infinite libraries, infinite technologies with no staying power) but also argues that humans have a history of borrowing from the past. Take Roman literature, Medieval icons being inspired by their Incarnation predecessors, and Chinese art deriving from itself. The kicker though is that even non-novel art always had a distinct expression. As he says, maybe we should “just accept that we are no longer modern, and have not been for a while”.

No way Jose: Air travel is the safest mode of transportation. A major reason is the intricate system of checks and balances, including stacks of documentation for each minute component that’s fitted, repaired, or replaced. And yet, one man gamed this system. This bonkers Bloomberg investigation revolves around a little-known aircraft parts distributor, AOG Technic Ltd, and its founder, Jose Yrala. Why “insane”, you wonder? One, because Yrala trampolined from being a techno DJ to becoming a supplier for some of the world’s largest aviation companies. Two, because it turned out that several employees with LinkedIn profiles were using stock photos and may not even have existed. Three, because AOG Technic Ltd pocketed millions of dollars in profits selling worn-out engine parts as new—meaning fleets on virtually every continent bear its unfortunate mark. Don’t miss this story for anything. Also read: how a shocking series of air traffic control lapses caused a near-collision at Austin-Bergstrom International Airport, Texas.

History Tragedy repeats itself: You’ll see parallels with Shakespeare’s King Lear if you’re the literary type. Or with the HBO hit Succession, if your tastes are more contemporary. But this story, as the Financial Times reports it, is as old as time. A dying patriarch, a prodigal son, and an acrimonious family battle over a vast fortune. The Safras, owners of the financial conglomerate Safra Group, are fighting over how to split up the $25 billion worldwide network of banks and other assets. Founder Joseph Safra’s son Alberto alleges he was cheated out of his rightful inheritance by his mother and brothers. His family insists it’s doing what the senior Safra wanted: to cut off his son for quitting the family business and setting up a rival. The Safras, Brazil’s equivalent of the Rothschilds, are notoriously private. They’re keen to avoid a trial in New York, where Alberto is expected to use medical records to prove his family took advantage of his mentally unfit father and change his wills. Succession and King Lear ended with the destruction of both empire and family. The Safra saga could be a retelling of this tragedy.

Storm’s coming: Death, taxes, and the looming threat of a crippling solar storm—these are life's certainties. The sun’s solar storms are like angry outbursts. Sometimes, they unleash 'coronal mass ejections,' supercharged particles hurtling 8,000 times faster than sound. When these reach earth, they can fry power lines, disrupt the internet via damaged undersea fiber optic cables, and clobber GPS and Starlink satellites, plunging humanity into chaos. The last such significant event was in 1989, and another is expected when the sun peaks in activity in mid-2024. A potential solution lies in AI that uses deep learning to predict storms by analysing solar wind patterns. But this demands continuous, high-quality data, which is in short supply because the Inouye Solar Telescope in Maui is the sole active observer. To find out more, check out this visual story in The Wall Street Journal.

You bet: The question “what will happen” is a human preoccupation from time immemorial. It could be tailored to any situation or event, but essentially the correct information has always been valuable. Weather.com built one of the most trusted brands in the world by deploying science to predict hail and storms. Prediction in reality is beyond rationality. Yet, a Silicon Valley movement called the Rationalists, comprising those who swear by data science, are reviving an old idea of prediction markets. They believe prediction markets can provide an accurate glimpse into what is coming, whether it is outcomes of elections, sporting events or for that matter anything. They believe the hive mind of the market near perfectly synthesises crowdsourced information. And because participants are betting, they have skin in the game and hence would be careful about the accuracy of the information they rely on. Analysts in finance and economics have also begun looking at prediction markets for a peek into the future. The New York Times has a fascinating account of a recent crystal gazers’ conference organised by forecasting startup Manifold Markets.